“Someone wrote to Satsvarupa Maharaja asking how on one week things would be so upbeat, and on the next a little down. He used to call that the roller coaster, and it rolled quickly. Now the pattern is slower, several days up, several days down. This seems to be the nature of the Parkinson’s disease. His legs might be stronger for several days, and he can be more helpful standing, or sometimes not. Some days he has swallowing issues, some days a little confusion with people’s names. Overall, though, the extra chanting and writing continues and even increases. He’s regularly reading Srimad-Bhagavatam with the devotees in the Zoom sanga. Old age is unpredictable, and we are rolling with it.

“Hari Hari,

“Baladeva”

The “News Items” section of Free Write Journal has been temporarily suspended while Guru Maharaja recuperates.

pp. 212-13

I’d like to remember the early days of Krishna consciousness with Swamiji at 26 Second Avenue. Those were the best times. Yes, I like to remember those early days. The special attention he gave me to bring me into Krishna consciousness. His being so exotic. Our Swami. Our kind leader on the Lower East Side. Taking us out of our hippie-dom into being devotees of Krishna, the pack of us, twelve of us. We became new friends, Hayagriva, Kirtanananda, Acutyananda, Michael Grant. The young movement. And then me going to Boston on your account, serving you in separation, writing you a letter every week, working in the welfare office for you. I was close to you then, guided by your letters, and you encouraged me. I like to remember our close association. You had so many disciples, even in the beginning, and you gave attention to each one of them. I’d like to remember that at the end.

I experimented with speaking extemporaneously over music to an audience. I did it at a Vyasa-puja meeting. I played jazz and classical music, and I talked about the spiritual world. I played a piece by John Coltrane called “The Wise One,” and it conjures up the guru, so I talked about Prabhupada. I played the ballad “My Funny Valentine” with Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan and came up with some emotions and expressed them. I was having a good time improvising and interrelating with the musicians and with my audience. I thought of the spiritual world to a piece of music by a classical musician and talked about what it might be like. It was an attempt at creative free expression, and I thought that it was successful.

I also did them without an audience and just recorded them. I sent them to Madhava to send out on the tape ministry. He liked them very much.

Recall eating lunch on the veranda at Mayapura with the GBC men. Brahmananda wolfing it down. Ramesvara politicking. Pancadravida joking. Throwing food. The food was delicious and served with reverence to us elite members. We ate with hearty appetites. Give me some more dal! They would come by with more capatis. It was blissful sitting out on the veranda. Prabhupada’s men. And then you would finish and wash your hands. Take some condiments.

I remember people coming to me, trying to get me to vote for a certain issue. Gopala Krishna Maharaja, Bhavananda, Ramesvara; all came to my room on different occasions and asked me to vote for something.

I liked going on harinama in Boston Commons in the summer when we had a temple of 60 devotees. We would go every day. We would take our lunch out there, too. Dal and capatis. We would keep a constant kirtana going and attract a crowd. Boys and girls together in the van. Hridayananda Maharaja. Rukmini. Baradraja. Saradiya. Vaikunthanatha. All of us singing together. Sacisuta and his wife. We put on a good show. It was lots of fun singing at the top of your lungs, holding off the cynical Boston crowd by the sheer energy of your voices and your Krishna consciousness in your dhotis and saris and your shaved heads. Every day we went out. Summer.

In 1966, Swamiji kept a jar of gulabjamuns which we called “ISKCON bullets” under his worship table and his worship room. It was understood that they could be taken by anyone who wanted one, who needed one at any time of the day. People who were breaking the smoking habit would go and get one. If I had a bad day in the welfare office, I would go and get one. They were delicious. You put the whole thing in your mouth, and it crushes sweet and drips out of your mouth and you’re zonked.

pp. 144-45

“One who is engaged fully with his body, mind, and speech in the service of the Lord is liberated even within this body, despite his condition.” (Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu 1.2.187)

Out of humility, the pure devotee does not think himself fit for liberation. He is willing to be born again in the material world, and his only request is that he be allowed to associate with pure devotees and not forget his beloved, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Although he does not serve for the purpose of going back to Godhead, the pure devotee’s mind and activities are so pleasing to Krishna that He brings His pure servant to Him for eternal association in the spiritual world.

Although the devotee’s services to the spiritual master are multifarious and easily award one liberation, they sometimes bring the devotee into direct conflict with the material world. These occasions provide tests of one’s sincerity and trust in Krishna consciousness. It is one thing to enjoy the liberated status of devotional service when one’s activities provide humorous contrasts to stereotyped ways of life. But when the execution of one’s spiritual duties seems to bring one only trouble, the tendency is to have second thoughts and in a different mood ask oneself, “Is this what I came to spiritual life for?”

Once while I was distributing books on a street in Tucson, Arizona, a storeowner assaulted me and broke my sannyasa rod over my head and shoulders. And once while singing in a kirtana at the Boston Commons, a thrown bottle hit me in the head. Many devotees have gone to jail for the offense of chanting Hare Krishna in public places. While living peacefully in their temples and asramas, devotees have been shot at and bombed. The news media regularly blasphemes and abuses the Krishna consciousness movement, and if a devotee decides to dedicate his or her life to Krishna consciousness, there is a good chance that he or she will be rejected by family, friends, and society.

Aside from tolerating the negative attitudes, a devotee must be responsible to push on the mission of Krishna consciousness in a revolutionary spirit. The Krishna consciousness movement is not quietism or mere armchair speculation. It is war against maya. Thus we can understand that liberation does not mean that one simply meditates “I am eternal” and does nothing. When Sanatana Gosvami, a learned disciple of Lord Caitanya, approached his master, he inquired, “You have said that I am already liberated; now what are my duties in the liberated state?”

Liberated duties may include arranging for marriage of disciples, providing for the raising and education of children, and struggling to raise funds for conducting and expanding a spiritual movement. One may ask, “Well, how does that differ from material life?”

The answer is that the Krishna consciousness, these seemingly material duties are undertaken not for anyone’s personal gratification but for the purpose of pleasing Krishna. One who willingly undertakes and who does not resent the headaches and entanglements which may result from practical devotional service in this world becomes very dear to Krishna and enters into an intimate relationship with Krishna in the spiritual world.

In an earlier essay, we quoted Prabhupäda’s aphorism “Deserve and then desire.” One cannot enter into his relationship with Krishna and the gopis simply by desiring, but one has to deserve this by the good credits of service unto the spiritual master. Therefore a devotee should never feel sorry if his devotional service leads him into many difficulties and burdens. One should be assured that these burdens are qualifying him and training him to become the eternal associate of Krishna. The more burden and responsibility one is willing to take for Krishna, the more dear he becomes to the Lord.

pp. 221-22

Vaiṣṇavas traditionally refer to a great soul by Sanskrit nomenclature such as nitya-siddha, jagad-guru, ācārya, mahā-bhāgavata, etc. How do these names apply to Śrīla Prabhupāda? Was he an incarnation? What was his rasa with Kṛṣṇa? We will review some of these terms and see how aptly they apply to Śrīla Prabhupāda.

Although out of humility, Prabhupāda never claimed to be a nitya-siddha, one who has never fallen down to the material world, Prabhupāda had the symptoms of such a great soul. One who is sādhana-siddha is a conditioned soul who is liberated by the performance of the rules and regulations of devotional service; and a kṛpā-siddha is one who attains liberation through the special mercy of the Lord or His pure devotee. But a nitya-siddha is extremely rare in this world.

Prabhupāda, like Uddhava, played with the forms of Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa as a child, bathing Them, feeding Them, and worshiping Them. He also held the Ratha-yātrā festival with his small playmates and would go across the street to visit the temple of Rādhā-Govinda daily. Prabhupāda said of himself that although he had ample opportunity to engage in sinful life, being born in an aristocratic family, he never did. “And throughout my own life, I did not know what is illicit sex, intoxication, meat-eating or gambling. So far my present life is concerned, I do not remember any part of my life when I was forgetful of Kṛṣṇa.”

In the Caitanya-caritāmṛta, Śrīla Prabhupāda writes of the nitya-siddha and the nitya-baddha (eternally conditioned). He states that the only business of the eternally liberated soul is to glorify Kṛṣṇa. Even if he appears to work like an ordinary man, in actuality, he is absorbed in Kṛṣṇa consciousness. Prabhupāda, like Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, was always Kṛṣṇa conscious, even though he did various kinds of work, especially in the early parts of his life. Śrīla Prabhupāda was certainly a specifically empowered jīva, who took the message of Lord Caitanya and distributed it throughout the whole world.

What about the claim that Prabhupāda was an incarnation? According to the Caitanya-caritāmṛta, unless one is empowered by Kṛṣṇa, one cannot propagate the saṅkīrtana movement. Kṛṣṇa-śakti vinā nahe tāra pravartana: “The fundamental religious system in the Age of Kali is the chanting of the holy name of Kṛṣṇa. Unless empowered by Kṛṣṇa, one cannot propagate the saṅkīrtana movement.” Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura explains that unless one is directly empowered by the causeless mercy of Kṛṣṇa, one cannot become the spiritual master of the entire world (jagad-guru). The spiritual master of the entire world must be considered an incarnation of Kṛṣṇa’s mercy.

Also, in Antya-līlā 2.13, we find: “To deliver people in regions throughout the universe who could not meet Him, Sri Caitanya Mahāprabhu personally entered the bodies of pure devotees.” In other words, one must be empowered by Lord Caitanya to spread the Hare Kṛṣṇa mahā-mantra throughout the whole world. Persons who do this can be called āveśāvatāras or incarnations endowed with the power of Sri Caitanya Mahāprabhu.

Śrīla Prabhupāda was also a representative of Lord Nityānanda. All spiritual masters are representatives of Lord Nityānanda, but again, Śrīla Prabhupāda was particularly blessed in disciplic succession because he saved so many Jagāis and Mādhāis. By the mercy of Lord Nityānanda, a devotee can excel even the Lord in service.

“Nityānanda Prabhu delivered Jagāi and Mādhāi, but a servant of Nityānanda Prabhu, by His grace, can deliver many thousands of Jagāis and Mādhāis… By the grace of Viṣṇu, a Vaiṣṇava can render better service than Viṣṇu; that is the special prerogative of a Vaiṣṇava.”

We should understand that our seeing Prabhupāda as a nitya-siddha and śaktayāveśa-avatāra, or our claiming that he was especially empowered by Lord Nityānanda, is not sentimental or concocted; by studying Śrīla Prabhupāda’s words and activities in relation to the scriptures, we can understand that these exalted designations are true.

pp- 11-12

On floor in here, tourist

folder for islands of Ireland. I don’t

want to take a currach to get to one.

Just stay in that house in south

or here. Quiet. Examine your mind—

empty of emotion.

Me, me, O little twinge. Read

Bhagavatam, then Migraine:

Everything You Need to Know, written

by a conservative, up-to-date RN who says

never overuse meds but doesn’t say

what to do. Little

paragraphs on alternatives,

one on T.M., one on yoga (not bhakti).

That Indian eye doctor asked me, “Do

you meditate or pray when you get a headache?”

What could I say? No, I didn’t think

I should. I just

strum, strum

Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna and fall silent.

I depend on His mercy

to take me.

Walked to the shed in green

rain paints—they will see that this

sannyasi doesn’t always wear his

official orange skirt.

The door was locked. I leaned

against the shed awhile and felt

pressure (like atmospheric clouds?)

in my head. Then walked back.

A mataji outside her camper—

can’t help her but

pranamas.

Back here with a stiff neck.

The quiet grows with the awareness

that I have no

prayer, not even any awareness but

to read. Bhaktivinoda Thakura’s purport

to atyaharah—so sensible, “Don’t do too much

or too little, and do it all for Krsna.” Yes, I say,

that I can do.

What, man, next? What, man, what? I have to follow

my own schedule propped up with med.

“There’s no R (relief) without D (damage),”

wrote one migraine sufferer.

Well, I feel pretty good now

on my way to a hot-cold shower and

lunch while hearing krsna-katha.

Bored, excited . . . Madhava told me

what books of mine are coming out.

I’m grateful. I don’t like cynical,

godless poetry. It would be nice if

we had Krsna conscious poets and artists and dancers and

could mingle like we did when young,

and feel we were authorized although

daring, free, experimenting .. .

But Krsna knows best. He’s fast and slow.

We have to die anyway. My brain can’t function

unless He wills. Got the philosophy

straight. But I skipped a

morning reading of Srimad-Bhagavatam

just too demanding—so

I wrote to you saying the grass out

my window and the peninsula of

Geaglum is delicious to see. It’s my

speed just to sit and sit

until my piles itch, unsentimental,

but spiritually inclined.

pp. 233-34

It has been raining this morning in Vrndavana. The tabletop is soaked again. I tilt the table and the water rolls off. Then I wipe it as dry as possible and sit to write. We are still without electricity. No loudspeakers! I can hear tremendous choruses of birds—and nothing else. If a bell rings or someone chants, it is only with the power of their own voice. Amplification needs electricity. This is what Vrndavana was like hundreds of years ago. But I am here now, groggy after my early rising, and aware of my dullness after thirteen mechanically chanted rounds. I did ask at several points why this had to be so.

“If we ignore Vrndavana, which is flooded with the nectar of Radha’s lotus feet and filled with the bliss of love for Lord Hari’s feet, then what are the other things we will talk about?” (Vrndavana-mahimamrta, Sataka 4.85).

Well said, good friend and great sadhu, Prabodhananda Sarasvati. Why talk of other things? Why ever forget Vrndavana? Even these rolling choruses of bird calls and chirping and peacock’s “kee-gaw” are part of Vrndavana. And the trees dripping in the rain. Who can complain about dark morning monsoon clouds in Vrndavana? Not me. But the symptoms of inattentive japa mean I have a hard heart filled with unredeemed aparadhas. I say I live with it. Others are worse than I am, I say. I look for encouragement in that fact and find it. Then I shake that off and turn to the sadhu:

“Srimati Radhika’s forest is the perfect atonement of sins, the ultimate shelter from offenses to great souls, the crest jewel of all principles of religion, and the crest jewel of all goals of life” (Vrndavana-mahimamrta, Sataka 4.88).

I sat in the darkness of my room. There was a little light from a high, barred window, but that light was really more of a lighter shade of darkness. It was similar to my mental conception of a dungeon. From my mat on the floor, I chanted and heard the japa of my two devotee friends in the other part of the house.

I can articulate better in writing, so here, on this page, on behalf of my japa-sadhana, I ask the Lord of Vrndavana to please help me. You make all arrangements in Vrndavana. I approach You through Your representatives, Vrnda-devi (who awards desires), Bhakti-devi, and Yogamaya. You have already given us so much mercy on this visit—this house to live in, permission to study and write, time to chant in peace. But if we cannot use it to love You, then what use is it? Please give me a clue as to how to find the essence.

“The fortunate bow down before a person who, always seeing the eternal and sweet spiritual forms of Vrndavana’s grass, bushes, and other living entities, and bowing down before them with great devotion, resides here in Vrndavana” (Vrndavana-mahimamrta, Sataka 4.90).

Prabodhananda Sarasvati has nistha for Vrndavana. I cannot imitate him, although I worship his statements. I hold them up, place them on my head as sacred. He is right! He sees the true Vrndavana. I cannot follow him in his advice to always live here—live like a wandering mendicant, bow down everywhere, serve everyone, see even the thieves as saints—but he knows there are persons like me, still in maya, but with a developing affection for Vrndavana. He offers us hope as we hear from him and build our own nistha upon his. He will not kick us away as hypocrites just because we are fools. But he will tell us plainly that we are foolish to abandon the dust of Vrndavana even for a moment.

pp. 27-28

(Today I put your beadbag on your hand, took off your old garland, and offered you a fresh one. You are friendly and receive this service from a tiny disciple.)

I know you are more than “friendly.” You have described that there is gaurava-sakhya, friendship in awe and veneration, and another kind of fraternity rasa known as visrambha, friendship in equality. I seek both in you. You are far more grave than I am, so I submit myself to you. I want to receive your instructions. Maybe I want you to encourage me to go on writing, but most important is that I please you. That’s the goal. What shall it be, Srila Prabhupada?

At least I’m coming to you in this way, enjoying your presence. The word “enjoy” usually carries negative connotations for devotees, but I want to enjoy serving you. I like your company.

When I left Prabhupada’s presence, I first bowed my head to his foot. Then I scraped the dust from the sole of his foot and put it on my head. How long I have been wanting to do this and missing it. I won’t miss it anymore. I also have been wanting to put my hands on his back and give him his daily massage.

Srila Prabhupada’s description of first-class devotional service:

anyabhilasita-sunyam

jnana-karmady-anavrtam

anukulyena krsnanu-

silanaṁ bhaktir uttamaWhen first-class devotional service develops, one must be devoid of all material desires, knowledge obtained by monistic philosophy, and fruitive actions. The devotee must constantly serve Krsna favorably, as Krsna desires.

“Krsna wants everyone to surrender unto Him, and devotional service means preaching this gospel all over the world. . . . The criterion is that a devotee must know what Krsna wants him to do. This can be achieved through the medium of the spiritual master, who is a bona fide representative of Krsna. . . . Therefore, one has to accept the shelter of a bona fide spiritual master and agree to be directed by him. The first business of a pure devotee is to satisfy his spiritual master, whose only business is to spread Krsna consciousness. . . . This process is completely manifest in the activities of the Krsna consciousness movement.

—Cc. Madhya, 19.167 and purport

There are so many people here that I can’t see your murti, Srila Prabhupada. They keep standing in my way. The marble floor is dirty from the feet of so many pilgrims. It empties out again for a few minutes and I catch a glimpse of you before the next group of pilgrims enters.

I don’t have to consider whether I like the architecture of the Mandir or the exact visage of your murti, I’m a worshiper, not a critic. This is where your divine body was placed in samadhi. I don’t have to understand the spiritual technicalities of “samadhi” when it refers to the spiritual master’s body to commune with your spirit. I just want to do that simply. I come here to worship, to see you (take darsana), and for you to see me—see me and plant new seeds in my heart. I want to serve you intimately. I need strength from you. You don’t grant intimate service unless we are deserving.

pp. 71-73

I confessed to Visnupriya that I think Harideva left me because I am too domineering. She says he didn’t leave me. She knows Harideva and I are close friends. She says he left to become purified. But she also told me that if I feel that I have not served my husband nicely, I should try to improve when he returns. She herself performs her duties happily for her husband.

People think of me as a faithful wife. “But,” I asked Visnupriya, “should we not also think that these marriages will soon dissolve?” She said that Lord Caitanya doesn’t much recommend householders to take sannyasa. But I thought, “What if your husband leaves and doesn’t come back?”

The fervor in our village has diminished somewhat, but the main things remain: We are all following Lord Caitanya. Throughout the village, people chant just as we saw Lord Caitanya chant. I don’t think that will ever fade. His mercy has gone too deep for that. We live in a tirtha. Radha-Krsna worship and krsna-katha are our life.

I feel sorry whenever I don’t think of Krsna. Our Deities are called Radha-Gopinatha. I am the first one to go to our little temple in the early morning. I open the door, light a lamp, and cleanse the floor with clean water. I sing softly so as not to wake the Lord and His Radha. After half an hour, the day’s pupil arrives to wake the Deities. Then people start coming; usually thirty arrive in time for mangala-arati. We stay for bhajanas and then a reading from sastra. Then I go for darsana at Laksmi-Narayarja Mandira. I pray for the protection of Harideva Prabhu.

It just occurred to me that I used to write this diary as a letter to my husband but now I have unconsciously stopped doing that. But even if I don’t address it to him in a personal way, I am mainly writing it to show him when he returns. I don’t consider myself complete without my husband.

Dear Harideva,

What I have just described are some activities I have taken up since you left. When you return, if you like, you can serve Radha-Krsna to your heart’s content. Ours is just a small temple, and there is no remuneration for the priests. All the brahmanas in this area take turns. I think if you want you may also resume your papri duties at Laksmi-Narayana Mandira. I don’t know for sure, but this is my guess. Everyone’s heart has softened; they appreciate that whoever serves Lord Caitanya is a devotee, and his past mistakes should not be held against him. But even if you decide not to serve at Laksmi-Narayana Mandira, everything can be accomplished here.

Maybe you prefer to travel and preach now that you have had a taste of it. I will do whatever you decide. In your absence, I am keeping myself busy in the temple. I have been collecting some of the pastimes of Lord Caitanya in order to share them with you when you return. I think you too will have nectar to tell. Sometimes I think I should go to join you, but I don’t know where you are or whether I would be welcome. Probably not. Tirupati and Dayananda are not willing to take me to join you either. So let us remain together in spirit, and for your pleasure, I will start to relate in my diary some of the pastimes of Lord Caitanya.

pp. 166-67

Write whatever comes and don’t end a session thinking this was not a good one. They are all good, and they all are “not good”—in the sense that I remain a tiny beggar with Krsna’s mercy on me. Gurudeva has the good qualities, the attachment to Krsna, and He can grant it to me. So thinking, “This session was particularly good” is still a kind of passion for results.

Or it may be that I sense Krsna’s mercy in a particular session. Okay, that’s okay. I’m just trying to encourage myself through a session like this one where it seems “nothing is happening.” To keep going at such times is important. Therefore something is “happening” when I insist on my practice, even through the desert. Haribol, haribol, we are chanting for the four directions, to the sun and the moon. We feel a chill, but what can be done? We have sold ourselves to Mukunda’s service in writing, at least for this hour.

Then when I go to japa, it’s even more pronounced that I need to keep trying even when I don’t get desired results. I surrender in that way. Again and again, with each bead and each word in each mantra, I fail to be attentive and devoted. Yet again and again I chant. This is my devotion and I love it, strange as it sounds.

St. John of the Cross and other practitioners of prayer have credited this persistence through arid times as a high order of surrender. There’s something to be said for it, even more than for times when we are tasting nectar. There’s no other choice for a neophyte except to persist or give up. He takes joy and satisfaction in persisting, even though there are no external signs of that joy. If someone suggests to him, Why don’t you give up chanting? Don’t do it if it’s just a guilt trip or a duty, he’ll find the devotee shocked and disgusted at the suggestion. “No! I will never give up japa (or writing). Even if it takes me many lifetimes to realize the nectar . . . I am not doing this to taste spiritual sense gratification, but because I am the eternal servant of the servant of the Lord and it is my constitutional nature to chant His names.”

Thank You Lord for this realization. That double-banded attitude of prayerfulness in japa is good—Thank You, and Please help me.

Hare Krsna Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna Hare Hare/ Hare Rama Hare Rama, Rama Rama Hare Hare. Sincere chanters appreciate sincere expressions by fellow chanters. They want to hear the perfect sastric statements on the glories of the holy name and its blissful effects. But they also like to hear from one who to his chanting seriously, even though he admits it’s a struggle, and he hasn’t tasted all the bliss “claimed” in the sastra. (One devotee criticized me strongly and at length when I said chanting was dry. I defended myself, but I can’t forget his criticism. Let it stay then and help me, but not weaken my determination—not only my determination to get the nectar, but to admit when I don’t get the nectar.)

Haribol. Time to go now. I like you, free-writer, and I like your chosen process of humbly writing whatever comes every day.

This collection of Satsvarūpa dāsa Goswami’s writings is comprised of essays that were originally published in Back to Godhead magazine between 1966 and 1978, and compiled in 1979 by Gita Nagari Press as the volume A Handbook for Kṛṣṇa Consciousness.

This second volume of Satsvarūpa dāsa Goswami’s Back to Godhead essays encompasses the last 11 years of his 20-year tenure as Editor-in-Chief of Back to Godhead magazine. The essays in this book consist mostly of SDG’s ‘Notes from the Editor’ column, which was typically featured towards the end of each issue starting in 1978 and running until Mahārāja retired from his duties as editor in 1989.

This collection of Satsvarupa dasa Goswami’s writings is comprised of essays that were originally published in Back to Godhead magazine between 1991 and 2002, picking up where Volume 2 leaves off. The volume is supplemented by essays about devotional service from issues of Satsvarupa dasa Goswami’s magazine, Among Friends, published in the 1990s.

Writing Sessions at Castlegregory, Ireland, 1993Start slowly, start fastly, offer your obeisances to your spiritual master, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. You just drew his picture with your pencils. He appears carved out of wood…

Last Days of the Year

Last Days of the YearI found I had hit a stride in my search for theme in writing, then began to feel the structure limiting me. After all, I had given myself precious time to write full-time; I wanted to enter the experience as fully as possible. For me, this means free-writing—writing sessions with no predetermined shape, theme, or topic…

aily Compositions

aily CompositionsThis volume is comprised of three parts: prose meditations, free-writes, and poems each of which will be discussed in turn. As an introduction, a brief essay by the author, On Genre, has also been included to provide contextual coordinates for the writing which follows…

Meditations & Poems

Meditations & PoemsA comprehensive retrospective of poetic achievement and prose meditations, using a new trajectory described as “free-writing”. This volume will offer to readers an experience of the creativity versatility which is a hallmark of this author’s writing.

Kaleidoscope

KaleidoscopeStream of consciousness poetry that moves with the shifting shapes and colors characteristic of a kaleidoscope itself around the themes of authenticity. This is a book will transport you to the far reaches of the author’s heart and soul in daring ways and will move you to experience your own inner kaleidoscope.

Read more »

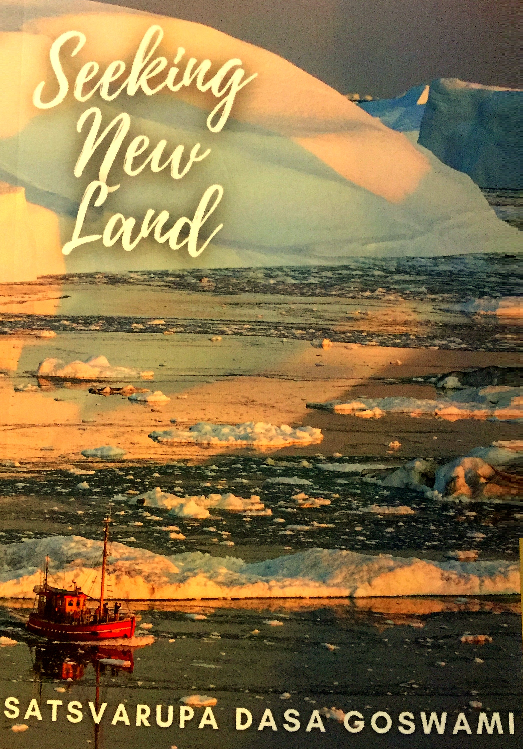

A narrative poem. challenging and profound, about the journey of an itinerant monk who pursues new means of self-Seeking New Land

A narrative poem. challenging and profound, about the journey of an itinerant monk who pursues new means of self-Seeking New Landexpression.The reader is invited to discover his or her own spiritual pilgrimage within these pages as the author pushes every literary boundary to boldly create something wholly new and inspiring.