Hari Hari! . . . .

This week showed a significant improvement with the frequent urgency for urination. The urologist’s magic pill seems to be doing its work; less frequency and more flow, which translates into longer periods of unbroken rest. On the downside, Satsvarupa Maharaja seemed to slide into a “rebound” situation with the frequent smaller headaches and use of Excedrin. What happens is that the Excedrin wears off, then sometime later a headache comes without any particular cause, and the cycle repeats itself. So to break the cycle he has to be on a Prednizone taper, which gives Satsvarupa Maharaja a week of no Excedrin and no headaches (if he doesn’t go over the twenty-minute limit of activity before resting again).

This is a graphic peek into “better living through chemistry” when you sign on to the allopathic team. Rest is best, but our patient has spent fifty years trying (successfully for the most part) to give up resting too much. Not being able to walk without assistance is actually much less of a recovery problem than the intense drive to keep writing at all costs, and the cost this time is headaches because of going over the twenty-minute restriction for concentrated activity of any type. This includes churning on what and how to write in the next piece. Yes, folks, it’s a mad drive to deliver Prabhupada and Krsna to those who read.

Hare Krsna,

Your servant,

Baladeva Vidyabhusana dasa

The “News Items” section of Free Write Journal has been temporarily suspended while Guru Maharaja recuperates.

SDG singing and clapping:

Hare Krsna Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna Hare Hare/ Hare Rama Hare Rama, Rama Rama Hare Hare

Good morning. It’s definitely summer now.

The other day I saw myself in the mirror and saw that I was dressed in my full sannyasi uniform—all saffron. Of course, I always dress in these clothes, but during the colder months, I usually have a gray or brown sweater on, and often I’m wearing a gray coat and a hat, things that make it a little less than the pure uniform. When I suddenly saw my image in the mirror, and my freshly-shaved head, I felt proud and happy to be an authorized ISKCON sannyasi. It’s an honor and one that I pray to keep.

This got me to thinking about other uniforms I have worn. They are a shame to me. For example, I remember feeling ashamed whenever I publicly wore my sailor uniform. That’s because usually people imagine a sailor to be a “jar-head,” a stupid guy who is almost always drunk. I wasn’t that kind of sailor, so it embarrassed me. I was a college graduate, an English major, a poet.

That’s the only other uniform, I suppose. Oh, I remember an episode about a baseball uniform too. I must have been fourteen or fifteen years old. The local police sponsored a league in our area and I went to the tryouts.

In those years, I was quite small. On the day of the tryouts, I made a mistake in the infield—maybe let the ball go through my legs, or something. I could never quite face a hard ground ball coming my way. I was always afraid I would get hit in the face. They let me be on the team, but they told me I wouldn’t get to play much. I had mixed feelings about that.

Anyway, that league wasn’t very well organized. Sometimes the coaches didn’t even show up. I was always punctual. If they said something was going to happen, I believed it.

One night, they told us we would practice and then go over to the sports store and get our uniforms. That was really exciting. I wanted that uniform so much. In those days, baseball players wore slightly baggy pants. All my major league heroes dressed like that. Getting that uniform would make up even for the fact that I couldn’t play.

After the practice, one boy after another was given his uniform. I waited and waited until the coach finally turned to me and said, “We don’t have a uniform for you. However, I can find pieces of a uniform here that you can use.” Then he gave me some hand-me-down gray baseball pants (the rest of the team had white) and a different kind of shirt than the rest of the team.

I was hurt and humiliated in front of the other boys, but I did my best not to show it. I don’t remember that they teased me. They were all so absorbed in their own uniforms that they didn’t pay attention to my rejection.

I went home and told my parents. “Look what they gave me.” My father thought if we bleached the pants they would turn white and look like everybody else’s, but it didn’t work. They were ragged and couldn’t take much bleaching. I attended a few games in that uniform and sat on the bench.

Then I found out in advance that one of the players was not going to be able to attend the next game. It occurred to me that maybe I could borrow his uniform for the game. He agreed. I was so grateful. While I was walking home, I imagined how I would look in the uniform. Then I put it on. That day, at least, I wore the uniform and traveled to the game. I wanted everyone to see me dressed as a regular player, if only for one day.

I didn’t play that well and the pitcher yelled at me. I was only put in at the end of the game because our team was so far ahead, but I made a mistake and they all got worried that they would lose their big lead. In the end, we won the game. I’ve thought about this story from time to time, but I never told it because I couldn’t see a Krsna conscious purport to relate it to. It occurred to me, though, that now I wear a prestigious uniform. Of course, it depends on what group you’re in. To college intellectuals, a kid’s baseball uniform doesn’t mean much. Similarly, to materialists, the uniform of a Hare Krsna sannyasi has no meaning.

I feel toward the sannyasa uniform as I did toward the baseball uniform. I may sometimes take it for granted, or even be shy when I’m wearing it in certain company, but at heart, I’m proud of it.

I prefer it to any other religious uniform, even a monk’s uniform, such as the classical Franciscan dress. We see many Franciscans here in Italy. They look quite tailored in their brown cloth hoods and rope belts. I prefer the lightweight, pleasantly colored dress of the Vaisnava sannyasi. This is almost like poetic justice for the humiliation I felt from being denied the baseball uniform or being forced to wear that navy blue jar-head suit. I hope I can always keep the sannyasa honor, the duties of sannyasa, and finally give even that up for the spiritual body and the spiritual dress most pleasing to Krsna, whatever that is.

As we hear the narration, we also hear about being on one side or the other, demons or devotees, and the differences. What need is there to cooperate with the demons? Why not have nothing to do with them? But that’s not always an option. When the demigods were weaker, they could not simply brush aside the demons, but had to work with them in order to defeat them in the end. Part of the victory meant first leading the demons on. Risky business. But this pastime also shows that Krsna protects us in the face of opposition from demons. If we’re not afraid and face the demons while taking shelter of Krsna, Krsna will protect us.

I don’t need to make a tally of each point as if it applies exactly to my own situation. I am taking this pastime as a general kind of symbol to show how the churning process can produce both poison and nectar, and how sometimes you have to declare a truce with your internal demons and then engage them to get at the nectar. It also points out how important it is to align yourself with the devotees, even if you happen to be “working with” the demons. In the instance of writing, that means not taking the viewpoint of an asuric free-writer who lets “everything” come out, with no regard to what it is and what its implications are. An asuric free-writer writes for sense gratification; I want to write for Krsna.

So again I am saying, when I start writing and powerful things appear, part of me may want to go with their energies. I don’t go with the energy in order to become a great writer or to revel in powerful imagery or because I think I’ve discovered some great universal secret; I trust that I know what to reject and what to accept, what is favorable for Krsna consciousness and what is unfavorable, and I trust that Krsna will protect me. I also accept that this is Krsna’s plan for me that I work in this way.

Ah! How can I say that my churning process is ordered by Visnu? The demigods were able to work confidently because they had received a direct order from Krsna. That’s probably the weak point in my analogy, that Krsna has ordered me to free-write. But I’m aware of the weakness. I’m always praying that I’m doing what Krsna wants. Somehow or other I am churning, so I pray to Krsna that He will guide me and protect me, and that in the end He will be pleased by the nectar that results. Krsna has not exactly appeared in my writing to enjoy His lilas with His devotees, but I am just one tiny, crippled servant who has found a method to write and who wants to serve Him with it, although it produces both poison and nectar. My whole life is based on the principle of trying to serve Krsna and my spiritual master. Therefore, when I serve, I have to apply my energy to serve. Whatever passion is in me comes out. Whatever ignorance is in me comes out. Whatever goodness is in me comes out. Then the transcendental nectar will also come and I will offer that to Krsna. Krsna will help me.

Aside from this specific image, the Vaisnava acaryas have given evidence that when we perform devotional service, weeds grow alongside the bhakti-lata. Lord Caitanya painted that image for us in His explanation of anarthas and aparadhas. When we perform devotional service, side by side with the auspicious spiritual growth of our devotional creeper, inauspicious weeds grow up. If we’re not careful to protect ourselves by distinguishing the weeds from the devotional creeper, we could allow the weeds to choke the creeper and fall down in spiritual life.

Becoming famous as a devotee—and attached to that fame— is an example of a weed growing with the bhakti-lata. But let’s examine how it comes. The devotee applies his energy to performing devotional service and there is some immediate result in this world. People may praise his piety or give him money. He may see other devotees with more facility and envy them. He may grow to like being worshiped, or to expect to be worshiped. Those desires were not part of his original intention to serve Krsna, but they are byproducts of his activities. All devotees have to learn how to deal with these unwanted desires. Krsna gives us the process by which we can learn devotional service, and it is filled with these kinds of tests: can we distinguish the weeds from the creeper and can we stay fixed on our watering of the creeper without being deviated by our love for the weeds? By Krsna’s grace, we can.

In Narada Muni’s instructions to Yudhisthira, a grhastha is advised to associate with saintly persons and hear about Krsna. He should not claim that these activities have to be given up because of daily work.

One should work eight hours at the most to earn his livelihood, and either in the afternoon or in the evening, a householder should associate with devotees to hear about the incarnations of Krsna and His activities and thus be gradually liberated from the clutches of maya. However, instead of finding time to hear about Krsna, the householders, after working hard in offices and factories, find time to go to a restaurant or a club where instead of hearing about Krsna and His activities they are very much pleased to hear about the political activities of demons and nondevotees and to enjoy sex life, wine, women and meat and in this way waste their time. This is not grhastha life, but demoniac life.

—Bhag. 7.14.4, purport

Narada advises that one should earn his livelihood “as much as necessary to maintain body and soul together,” and continue a detached attitude while living in human society. Prabhupada comments:

A wise man . . . concludes that in the human form of life he should not endeavor for unnecessary necessities, but should live a very simple life, just maintaining body and soul together. Certainly one requires some means of livelihood, and according to one’s varna and asrama this means of livelihood is prescribed in the sastras. One should be satisfied with this. Therefore, instead of hankering for more and more money, a sincere devotee of the Lord tries to invent some ways to earn his livelihood, and when he does so Krsna helps him.

—Bhag. 7.14.5, purport

Narada also advises one not to be a thief and claim proprietorship of all his wealth, but spend extra money for advancing oneself in Krsna consciousness.

The grhasthas should give contributions for constructing temples to the Supreme Lord and for preaching of Srimad-Bhagavad-gita, or Krsna consciousness, all over the world. . . . The Krsna consciousness movement therefore affords one such an opportunity to spend his extra earnings for the benefit of all human society by expanding Krsna consciousness. In India especially we see hundreds and thousands of temples that were constructed by the wealthy men of society who did not want to be called thieves and be punished.

—Bhag. 7.14.8, purport

Narada advises King Yudhisthira and all grhasthas to avoid ugrakarma, work which is hellishly difficult, risky, and implicated with sin. Prabhupada comments:

Men are engaging in many sinful activities and becoming degraded by opening slaughterhouses, breweries and cigarette factories, as well as nightclubs and other establishments for sense enjoyment. In this way they are spoiling their lives. In all of these activities, of course, householders are involved, and therefore it is advised here, with the use of the word api, that even though one is a householder, one should not engage himself in severe hardships. One’s means of livelihood should be extremely simple.

—Bhag. 7.14.10, purport

Those devotees who donate their money for spreading Krsna consciousness are as meritorious as the devotees who actually spend the money in preaching activities. If a worker is hesitant to hand over his hard-earned money to the local temple, he can spend with his own hand for a worthy Krsna conscious project or a project which he directs himself. One can buy Prabhupada’s books and distribute them, or send money to foreign missions of Krsna consciousness. Spending money for the spiritual development of one’s own family members, by setting up Deity worship in the home, or by taking one’s family on pilgrimage to the holy dhamas in India are all good ways to spiritualize earnings and to purify the sacrifice of work. As Lord Krsna states, “Work done as a sacrifice for Visnu has to be performed, otherwise work causes bondage in this material world.” (Bg. 3.9)

Srila Prabhupada rose early in the morning and spoke alone to Krsna; through his books he shared these “conversations” with the whole world. His purports are a special, intimate communion with him, and through them, we can know Krsna.

We can gain more appreciation for Srila Prabhupada’s books just by understanding how much time and effort he put into writing them for our benefit. He personally typed the First and Second Cantos of Srimad-Bhagavatam on his small, portable typewriter. Later, he began to dictate the verses and purports onto tapes and mail them to the typist. He rose early, usually around 1 a.m., and in the quiet of those early morning hours, he would absorb himself in the voices of the previous acaryas and then present their words for the common understanding of the world.

Prabhupada said, “The purports are my devotional ecstasies.” Ecstasy was a very important part of Lord Caitanya’s influence in preaching. Stern warnings from preachers may not prompt us to leave the material world, but the ecstasy of the Lord and His devotees can attract us. We can get a taste of that ecstasy if we submissively study Srila Prabhupada’s books.

There are many other statements made by Srila Prabhupada to describe the importance of his books. He said, “My books will be the lawbooks for human society for the next ten thousand years,” and, “So there is nothing to be said new. Whatever I have to say, I have spoken in my books.” “My purports are liked by people because it is presented by practical experience. It cannot be done unless one is realized.” He told his disciples to “cram” his purports and that writing is the first duty of a sannyasi. And he told the book distributors, “My books are like gold. It doesn’t matter what you say about them. One who knows the value, he will purchase.”

The Bhaktivedanta purports are based on the commentaries of the previous acaryas. SrilaPrabhupada would work from a Bengali translation of the Bhagavatam, with commentaries by twelve acaryas, such as Visvanatha Cakravarti, Jiva Gosvami, Sanatana Gosvami, Sridhara Svami, Bir Raghava Gosvami, Madhvacarya, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, and Bhaktivinoda Thakura. The Bhagavad-gita is dedicated to and follows the commentary of SrilaBaladeva Vidyabhusana; the Caitanya-caritamrta purports are summarized from those written by Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati and Bhaktivinoda Thakura.

Even if we consider that Prabhupada’s purports are partly translations of previous commentaries, this does not diminish our gratitude for his preaching and giving us access to the thoughts and devotion of the disciplic succession. Once, the devotees were commenting on how quickly Prabhupada was writing. Prabhupada said, “Oh, I can finish very quickly, but I have to present it for your understanding. It requires deep thought, very carefully to present.”

And neither were his purports just static translations of other commentaries, but he struggled to apply the words of the previous acaryas to the present-day mentality of the Westerners. We can imagine how difficult this must have been—trying to present the principles of Vedic government, or the position of women in Vedic culture, or even the necessity to avoid sinful life—to persons who were addicted to sense gratification and who had no idea what was wrong with it. He saturated his purports with Krsna, and built the groundwork to supply his readers with the cultural language to enable them to enter into the pages of the Bhagavatam.

Vrndavana is the place where

I beg for extra mercy,

although part of me says cut

back and just do what you

can. Don’t ask for an opus,

just write one book at a

time. “Beggar,”

I say

I’m a beggar, but not

blind or crippled and

sitting by the roadside in

my British scarf and

long johns. Not that kind of beggar

but a beggar for sure.

I have no niche in Vraja,

yet still I ask, “Please let me

write or

whatever

You want.

Vrndavana is calling me and I

respond with a prayer for a service

I can take with me when I leave. May it be

Vrndavana-centered, a Vrndavana

series of books to write.

May I be faithful to Vrndavana

Krsna wherever I go.

I’ve got a children’s

“Dreamland” series,

picture books with narration

from Srimad-Bhagavatam Tenth Canto.

I use it for collages alongside my

stick-figure children and bhaktas

and parrots. May I be faithful

to Sri Vrndavana dhama.

O Lord, Radha-kunda is in Vrndavana

and is cold in January.

Sadhus still walk around

Govardhana—pilgrims in eternal

Vraja. If I don’t go out

there on this visit, it may be

I’m not ready. Please guide me.

I want to be a good devotee.

I want to write, write in my

last years, a book

I will love to do and to share

with others.

In Vrndavana

I’m happy to stay in my room

“always something reading and writing,

something reading and writing.”

I’m too fragile to go out—catch colds and get

headaches.

I can stay here all the time and

answer letters, plan new books—

no end of things to do.

This is Vrndvana too.

Its blessings come through the walls.

I woke at midnight to

thunder, lightning and rain.

Early start to japa, but

it was sluggish and mechanical.

Nevertheless I did them all

rapidly and awake. I lacked

the inspiration for a japa meditation.

Had them all counted by 3:00 A.M.

The conditioned souls under the

spell of illusion suffer three

kinds of miseries: adhyatmic, caused

by the mind and body, adhibhautic,

caused by other living entities,

and adhidaivic, caused by

natural disasters under control

of the demigods. If by chance

one meets a pure devotee and

follows his orders, he can be

delivered from all these pangs.

The room is quiet and warm,

too early for birdsong.

Today I’ll finish the drawing of

three sadhus looking out with

bead bags and renunciation.

The autobiog. is dormant and

may be finished. I’ll have

to think of another way

to write.

A yoga class was being

held across the street.

Saci was running in a

race in Albany.

I was biding my time

in-between projects.

I have a morning

poem which shares

melody from my

musical soul.

It’s expressed out of

a need to sing and

a desire to entertain

poem readers with

divided lines.

The song is Krsna offered from a

servant’s life,

a little life,

a small accord,

placed at the lotus feet

with care and good intention.

tasyaivaṁ khilam atmanaṁ

manyamanasya khidyataḥ

krsnasya narado ’bhyagad

asramam prag udahrtam

As mentioned before, Narada reached the cottage of Krsna-dvaipayana Vyasa on the banks of the Sarasvati just as Vyasadeva was regretting his defects.

Srila Prabhupada states that the void Vyasadeva felt was not due to lack of knowledge. Prabhupada’s statement, “Bhagavata-dharma is purely devotional service of the Lord to which the monist has no access” almost hints that Vyasadeva was in a position similar to an impersonalist. Of course, Vyasadeva was never an impersonalist, but the fact that he did not fully concentrate on glorifying Krsna but stressed religiosity and jnana indicates that his books so far were less than bhagavata-dharma. It stands to reason that if a work does not present pure bhagavata-dharma, it must contain to some degree karma and jnana.

Although impersonalism is a heavy charge, we may lean toward impersonalism not only by teaching Sankara’s speculations, but simply by not openly acknowledging Krsna’s transcendental form and pastimes. Anyone who claims to speak Vedic knowledge but doesn’t refer to Krsna the person is omitting something vital from his talks. We see with scholars who remain neutral and who comment on the Bhagavad-gita without teaching surrender to the Personality of Godhead that Krsna regards them as fools. Srila Prabhupada refers to Vyasadeva’s regret as “inspiration . . . infused by Sri Krsna directly in the heart.” Inspiration, or Krsna’s dictation through the heart, doesn’t always come as a discovery of something wonderful; we may also see our defects. We heard in the previous verse Vyasa’s diagnosis of his own fault. Now Srila Prabhupada informs us that this insight was inspired by Krsna.

Inspiration appears miraculous. Suddenly our strength to understand or to do something exceeds our usual capacities. Vyasa was bewildered but suddenly understood what he could not grasp while recording the Vedas. And what an inspiration! To understand that without describing the transcendental loving service of the Lord, everything is void.

Another point to note in this verse and purport is Vyasadeva’s expression of regret. Without experiencing regret we cannot experience reform. Reform means more than simply giving up a bad habit for a better one; it implies a changed heart.

There are many examples throughout the scriptures of the purifying effects of regret. Maharaja Pariksit also regretted neglecting to honor Samika Rsi. Prabhupada writes, “Repentance comes in the mind of a good soul as soon as he commits something wrong.” (Bhag. 1.18.31, purport) And again, “ . . . by the grace of the Lord all sins unwillingly committed by a devotee are burnt in the fire of repentance.” (Bhag. 1.19.1, purport)

A pure devotee regrets any moment in which he is not thinking of Krsna or engaging in His service. “The exchange between Vidura and Uddhava exemplifies this point:

On the inquiry by Vidura about Krsna, Uddhava appeared to be awakened from slumber. He appeared to regret that he had forgotten the lotus feet of the Lord. Thus he again remembered the lotus feet of the Lord and remembered all his transcendental loving service unto Him, and by so doing he felt the same ecstasy that he used to feel in the presence of the Lord.

—Bhag. 3.2.4, purport

Regret induces a heightened state of spiritual remembrance, and remembrance takes us into Krsna’s presence. Vyasadeva entered an inspired state when Krsna allowed him to feel his emptiness. His regret that his previous works were not tangibly Krsna conscious impelled him into the transcendental service of the Lord where “everything is tangible without any separate attempt at fruitive work or empiric philosophical speculation.”

It would be nice to think that when we are spaced out or empty, it is Krsna’s way of trying to awaken our remembrance of Him. Of course, to say that and for it to be true, we have to respond to Krsna’s prodding. Simply to be drugged by the mode of ignorance is not a blessing. But if somehow we are stung into awareness of our forgetfulness, our empty hearts, that is a blessing. All blessings come directly from Krsna and His devotees. Krsna is in our hearts, and He awards our desires. If we repeatedly indicate that we want to forget Him, He will put us into a state of forgetfulness. If while in the forgetful state we suddenly feel the emptiness of a life without Krsna, that becomes the blessing, and it is His causeless mercy.

This collection of Satsvarūpa dāsa Goswami’s writings is comprised of essays that were originally published in Back to Godhead magazine between 1966 and 1978, and compiled in 1979 by Gita Nagari Press as the volume A Handbook for Kṛṣṇa Consciousness.

This second volume of Satsvarūpa dāsa Goswami’s Back to Godhead essays encompasses the last 11 years of his 20-year tenure as Editor-in-Chief of Back to Godhead magazine. The essays in this book consist mostly of SDG’s ‘Notes from the Editor’ column, which was typically featured towards the end of each issue starting in 1978 and running until Mahārāja retired from his duties as editor in 1989.

This collection of Satsvarupa dasa Goswami’s writings is comprised of essays that were originally published in Back to Godhead magazine between 1991 and 2002, picking up where Volume 2 leaves off. The volume is supplemented by essays about devotional service from issues of Satsvarupa dasa Goswami’s magazine, Among Friends, published in the 1990s.

Writing Sessions at Castlegregory, Ireland, 1993Start slowly, start fastly, offer your obeisances to your spiritual master, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. You just drew his picture with your pencils. He appears carved out of wood…

Last Days of the Year

Last Days of the YearI found I had hit a stride in my search for theme in writing, then began to feel the structure limiting me. After all, I had given myself precious time to write full-time; I wanted to enter the experience as fully as possible. For me, this means free-writing—writing sessions with no predetermined shape, theme, or topic…

aily Compositions

aily CompositionsThis volume is comprised of three parts: prose meditations, free-writes, and poems each of which will be discussed in turn. As an introduction, a brief essay by the author, On Genre, has also been included to provide contextual coordinates for the writing which follows…

Meditations & Poems

Meditations & PoemsA comprehensive retrospective of poetic achievement and prose meditations, using a new trajectory described as “free-writing”. This volume will offer to readers an experience of the creativity versatility which is a hallmark of this author’s writing.

Kaleidoscope

KaleidoscopeStream of consciousness poetry that moves with the shifting shapes and colors characteristic of a kaleidoscope itself around the themes of authenticity. This is a book will transport you to the far reaches of the author’s heart and soul in daring ways and will move you to experience your own inner kaleidoscope.

Read more »

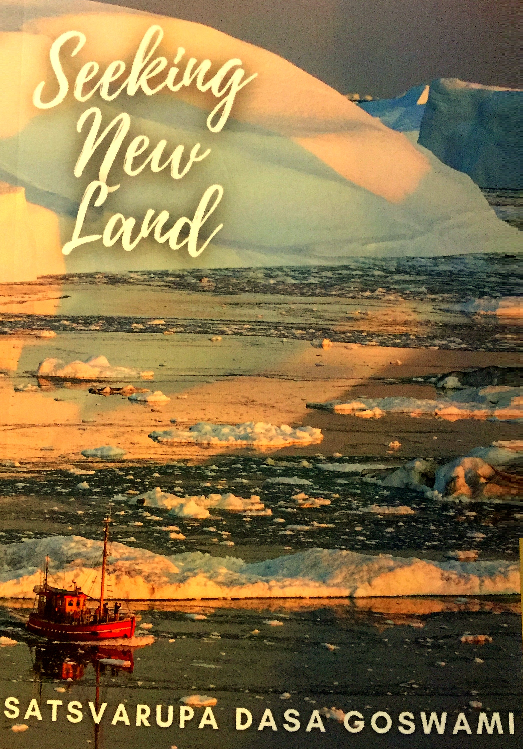

A narrative poem. challenging and profound, about the journey of an itinerant monk who pursues new means of self-Seeking New Land

A narrative poem. challenging and profound, about the journey of an itinerant monk who pursues new means of self-Seeking New Landexpression.The reader is invited to discover his or her own spiritual pilgrimage within these pages as the author pushes every literary boundary to boldly create something wholly new and inspiring.