If you would like to help, please contact Kṛṣṇa-bhajana dāsa at [email protected] or [email protected] and we will find you a service that utilizes your talents.

Now let me go and read some section of Namamrta and see if I can find some quotes. Of course, the quotes are not the actual experience, not the actual life of my day-long chanting. I chant perhaps almost nine hours on this sixty-four rounds a day vrata, and I don’t think of the glories of the holy name as enunciated in the sastras. I just plug along as I’ve described. But still, one can’t just talk about such mechanics in a gathering. Let’s hear the glories of the holy name. It’s because of those glories, because of the sages and the sastras and what they say about hari-nama that we’re able to have faith and keep going with it. We go on the strength of Vedic injunction and because Prabhupada says so. This is more important than what I experience during my nine hours. Hare Krsna.

******

Last night at our meeting, I first played a tape by Srila Prabhupada in which he said bhagavad-bhakti-yoga has been made very simple and easy by Lord Caitanya. Just chant Hare Krsna. Prabhupada then explained the verse of Siksastakam that ends by saying the unfortunate class of persons commit offenses and don’t have taste for the chanting. Then I told how I had felt positive during the day, but the chanting is it, not a mere approach to God or discussion about Him. It’s Krsna in the most direct form. We may not taste the bliss, but if we want direct access, this is it. Nothing else needs to be done but chanting.

I then read a quote from Namamrta that if one chants offenselessly, he becomes qualified to initiate disciples all over the world; he is jagad-guru. I don’t claim I am that, but it’s proof that a guru requires this. His disciples then become attracted to chanting, and when he sees this he is in ecstasy. Another quote says a sannyasi need do nothing else but always chant Hare Krsna. I read the Second Canto verse on “steel-framed heart.”

******

Manu said it was his steadiest day so far. He read some quotes. Bhakti-rasa read and spoke his appreciation for the simplicity of this practice. He said this week is teaching him for the first time that Krsna consciousness can be attained just by chanting, and that we actually can do it and don’t have to do anything else.

I said I discovered mechanical chanting as a stage beyond direct indulgence in inattention. “Mechanical” here means attentive to the mechanics, and it’s not a bad thing. But of course, it’s not yet done with the heart.

******

While you can, chant. While the blood flows within the body and the bones are not cracked and you are not dead—chant.

Sure, there are many other services. I said it’s probably common in ISKCON to chant the sixteen rounds inattentively and get them out of the way. But this week we have gone beyond that. Since our vow is to do sixty-four each day, you can’t chant thinking, “I’ll get them out of the way as soon as possible and go on to more important activities of the day.” The chanting is the main activity.

******

Vrata consciousness we can continue after our week is up. Our quota will go down to sixteen. Or can we keep a little increase? Can we stay above that offensive level of deliberate inattentive chanting where we mull over and live in our thoughts, with the japa a mere background noise? I hope that there will be a continued improvement in my case. I’m not an all-out lover of the holy names. But I do understand it is the most important (Prabhupada and the sastras say so) and it is the easiest access to love of God. Who but a stubborn fool will avoid it?

******

Hare Krsna Hare Krsna, I will not abandon Thee, precious mantra given to me by my spiritual master. I will chant You all the days of my life, until and including the hour of my death.

Please stay with me, holy names. I don’t know anything. I need your love. You are God in most convenient form.

I embrace you, harer nama. You reciprocate.

You are given to me in disciplic succession.

Hare Krsna is my days and nights. On beads he gave me. My Swami, my leader has kindly said, “Chant Hare Krsna.” We are writing and that’s good too. But don’t neglect your chanting.

******

Aware of that power to affect change and decide what you can and can’t do. In regards to chanting Hare Krsna mantra, however, you can rest assured that there will never be a resolution forbidding it. As for impetus to do it, that will come from your own practice and relationship with your spiritual master and with hari-nama.

******

Half hour’s walk from here is a little shack by a man-made lake. A sign outside the shack reads, “Pibbles Fishing Club.” We are in the Hare Krsna chanting club. We fish for better chanting. We go on “fishing” all day long. Sometimes we see a fish jump out of the water—and inside into the ecstasies. Sometimes we catch a fish. (Drop the metaphor, because chanting isn’t killing anyone. One doesn’t like to compare this inoffensive, sweet act of surrender with hooking the fish. I just wanted to write, and that image came to mind.)

******

Preserve your energies. Start in the days counting and chanting and uttering. It’s work all the way. No single mantra is very difficult, but there are so many you have pledged to make, so you have to work at it almost constantly until 5 P.M. Then an hour “free time” and then the 6 P.M. meeting—which lasted for an hour last night—and then to bed for sound sleep. Full day’s engagement.

Thank you for writing it down.

Okay, see you later.

pp. 11-12

While K. Prabhu gave the Srimad-Bhagavatam class bundled up in a white turtleneck sweater, I sat on the edge of the crowd, also bundled warm. Our eyes met, he gave a little nod of recognition, which I also did, and the class went on. He was saying something about total surrender and Krsna wants nothing less than that. I thought it was too much pressure. Who is going to do it? Who will we trust in Krsna’s place to tell us, “Do what He asks”?

G.S. likes my approach—give a person confidence in themselves and they will surrender out of love. Know who you are, don’t be afraid to express who you are and give your best “self” to Him.

Prabhupada said that theism isn’t only to say, “I believe in God”; we have to accept the Vedic injunctions and directions.

Push me, O Krsna, Your aspiring bhakta. I heard a brother went all the way to Surinam, distributed seven thousand pieces of prasadam, collected money, lectured, and desired so strongly to deliver Krsna consciousness despite all bodily inconvenience that he succeeded. I have to do something equivalent.

Srila Prabhupada: “The basis of change is the individual.” We change ourselves, then the world. I agree with that. We have to face not only social issues but the personal issues of authenticity, surrender, freedom, creativity—and failure.

You will have to walk down the narrow cement passageway between Prabhupada’s house and the wall of the Krsna-Balaram Mandir. All ISKCON devotees have to pass through. All persons who are in this Gaudiya line. People, too many for me to comprehend. Get away from playing the role of the monk so you can become the monk. You are a person you don’t know. As Sanatana Goswami said, “They think I am learned, but I don’t know who I am—ke ami?”

All hail, the individual versus the mob. Quote Soren Kierkegaard on this. I’m saying everyone in Belfast is a potential devotee, “That Individual.” And you cannot expect to take it as a group but take it for your own reasons. Take it deeply and purely, and then you can preach.

I’ve got my filters and selective memory lapses and all sorts of maladies. Do you want to own someone? You can’t. Just be a friend. Don’t be possessive, jealous. Don’t ask the whole world to say, “You’re the best.” You feel threatened when someone writes like you. You feel anxious when you find something to chew on, chew, chew, chew until you get a headache. Can’t sleep, can’t cheep in the morning, and worst of all, you know what’s worst of all . . .

His sadhana has crawled down into a hole. A deep wormhole, and we don’t know how to get him out. It’s terrible. Yet he says, “I’m happy. I like living in Wicklow.” He’s a hypocrite, he’s got his anxiety disorder on the plate with couscous and beans, things he doesn’t like to eat. Here’s some tofu. But I told you a million times I don’t like tofu or pasta, or the way you guys make pancakes. Maybe I just don’t like pancakes period. Someone is thinking of entering a deeper life of sadhana, maybe going to Vrndavana. You hear it and say, “Can I come along? Can I make the mystic journey too?” No, not likely. You’re a twerp and a chewer, and subpar japa. You can’t even confront the monkey hoards without fear down your spine. They grin at you, you smack your bat. I just want to live in heaven with God and His parishads and nice monkeys.

The simple, direct hookup is the intensive care of mantra-chanting. This hookup was supplied by a guru who will never abandon me. Don’t, therefore, be attached to physical pleasure or pain. Tolerate everything. It’s all temporary. Pray that Krsna becomes your all-in-all.

pp. 120-24

Although Prabhupada was worlds apart from the young people in America, the younger generation accepted him as “cool”; he was hip in his own way. He was not a middle-class conformist, and he had not come to give us Boy Scout lessons. He was not a church minister giving sermons with a piety that we could not relate to. . . . We must never forget that Prabhupada was able to establish intimacy with hundreds of persons. He did not merely give us lessons in perfection delivered from a mountaintop. Rather, his physical association was always nearby. He had a small room, we sat close to him; we shared his food, bought clothes for him. The awkwardness of not trusting him soon changed, and he also reached forward and pulled us toward him in a spiritual relationship.

Srila Prabhupada removed the awkwardness by convincing us that we did not belong to a different religion than he. He referred to the transcendental level at which all things come together. He used to say, “No one should object and say that they can’t chant Hare Krsna because it is a foreign name and it is not one’s own religion. This is transcendental sound vibration. We are all spirit souls, parts and parcels of Krsna.” In this way, he established spiritual intimacy.

San. They were illusion, based on false designation. Thus he gave a new consciousness and a new way to see reality.

The awkwardness of those early days was also expressed in our feelings at first taking on the dress of the Vaisnava and the shaved head and sikha. So much awkwardness! Not knowing how to pronounce the Sanskrit, not being able to spell or chant properly—gradually these things were overcome. Prabhupada did not push them on us.

As for Srila Prabhupada’s own unfamiliarity with Western culture, it was a feature that simply made him more dear to us. If he did not understand the use of a word in the English or American language, it was another occasion to love him. One time a devotee told Prabhupada that he might get fired from his job. Prabhupada was astonished and said, “Fired? They would fire on you?” Prabhupada thought the devotee would be fired with a gun. The devotee replied, “Oh no, Prabhupada! ‘Fired’ just means they would release me from the job.” We would all laugh together about his not knowing these words. We did not expect him to know such things, but neither did we think of him as a “foreigner.” Prabhupada knew the transcendental world, the real home. To be unaware of the material world was just another sign of his detachment. We did not expect that eventually he would educate himself in such things. He was not interested. They were all in the category of ignorance and passion.

Awkwardness was overcome. The all-important first step was to learn the words to the maha-mantra—Hare Krsna Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna Hare Hare/Hare Rama Hare Rama, Rama Rama Hare Hare. Once we got that straight, everything became easy and natural. When you think about the fact that within a few months a new devotee feels familiar with the philosophy and with Prabhupada, it makes you think that maybe it really won’t take so long to feel at home in Krsna consciousness and to develop a desire to go back to Godhead.

I told the spiritual youngsters here

that you are their siksa-guru.

That was OK, but later

I thought how I write like a buffoon.

Would I dare to speak this way in your presence?

No.

I reasoned it out: when I praise you it is truer

than when I just recite generic

praises to the Vaisnava guru.

I said, “Unless you know

the way Srila Prabhupada did things

you can’t be a responsible leader in ISKCON.”

I told them to become aware of Prabhupada.

The lecture goes

into my spiritual bank account.

But there are withdrawals,

such as when I envy your men.

Prabhupada, thanks to you

I am still your servant.

I am striving,

and you include me.

What do they do who

think of you always?

I don’t know.

Some devotees are dedicated to you

in pure, strong ways. Your missionaries.

I never seem to get enough.

I fell asleep during so many of your lectures,

in LA., Bombay,

I was tired from work for you,

but that is no excuse.

You said, “I notice you fall asleep.”

I said, “I don’t want to.”

You said, “Some people in India say Srimad-

Bhagavatam is a sure cure for insomnia.” Let it

not be true!

I placed the netting nicely around your bed,

tucked it in everywhere so no mosquitoes

could get in. Then you rested and

I rested a few feet away.

I waited for your next sound,

which was soon.

Waking me from sleep.

I ate your food remnants again and again,

chewed oranges, the dal, rice and sabji

mixed together as maha-prasadam.

It’s not just food.

Once your servant came out of your room

carrying your maha on a silver plate.

The devotees knocked him over,

ravaged the plate.

“Once only, by their permission, I took

the remnants of their food, and by so doing

all my sins were at once eradicated.”

pp. 84-89

By the time I transferred to Brooklyn College, most of my courses were in my major, English Literature. It could be said without much exaggeration that most authors are ruined for students when read within the college course. It is a terrible setting for actual learning. For myself, whatever juice I got from books was mostly done in extracurricular reading, without the pressure of exams and grades and without having to memorize and submit to an “authorized” version of the poet’s worth and meaning.

Coming from Staten Island, I wanted to prove myself worthy in the academic big leagues, and so I became a dancing dog. I strived to get all A’s. “Walt Whitman, are you going to stand in the way of my getting an A, or will I be able to claim you for my purposes? Emily Dickinson, please don’t hide your inner life from me, because I have to make clear sense out of you for my final exam.” I don’t have much live remembrance of these authors, probably because I’ve studied them within the syllabus of American Literature 101. I know that Emily Dickinson is supposed to be brilliant, transcendental, one of the greatest poets of all time — and I know Whitman has been a direct inspiration for generations of American poets. But for me they remain mangled as school subjects.

When I studied Hamlet with Prof. Grebanier, the big question — which he said puzzled all the inferior scholars—is why did Hamlet hesitate to kill his father’s murderer? Everyone had their own opinion about it. Some said that Hamlet was wishy-washy, some said that he did not have sufficient criminal evidence, or that he was too philosophical, and so on. Well, it no longer seems to me to be a deep issue. Even if we get the right answers, whose life will be improved? The questions in the bona fide scriptures, by comparison, are crucial and relevant for everyone’s welfare. In the Vedic literature Maharaj Pariksit’s dilemma was, “What is the duty of one who is about to die?” And the question asked by Maharaj Yudhisthira (and at another time by Maharaj Prithu) was, “How can we, who are householders and involved in worldly duties, come out of the entanglement of birth and death and achieve spiritual perfection?”

Hamlet asks the question, “To be or not to be?” But he never asked, “Who am I?” He saw the ghost of his father, but he never consulted with a bona fide saintly person who could have raised the issues to the transcendental platform for everyone’s benefit, including those who watched the play. Hamlet is tragic, as is all material life. And certainly Shakespeare spoke like an empowered demigod with abilities for poetic philosophical expression that have rarely been equalled. When all is said and done, in Act V we get a heavy bed load of the dead, but what wisdom? Where is that Hamlet where the hero — like Arjuna of the Bhagavad-gita is told that he is considering everything on the bodily platform and that there is a higher truth? Where is that Shakespeare masterpiece where the spirit soul inquires from the guru, “What is my duty?” We want to see that play. That is our demand. Hamlet is not transcendental.

When we look at Hamlet from the spiritual perspective (just as when we look at Holden Caulfield), he appears to be a very likely candidate for spiritual knowledge. Consider his famous speech in which he agonized about the temporality of human life.

I have of late, but

wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth, forgone all

custom of exercises, and, indeed, it goes so heavily

with my disposition that this goodly frame, the

Earth, seems to me a sterile promontory; this most

excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging

firmament, this majestical roof, fretted

with golden fire—why, it appeareth nothing to me

but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors.

What ⟨a⟩ piece of work is a man, how noble in

reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving

how express and admirable; in action how like

an angel, in apprehension how like a god: the

beauty of the world, the paragon of animals—and

yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? Man

delights not me, ⟨no,⟩ nor women neither, though by

your smiling you seem to say so.

(Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2)

Brooklyn College had nice lawns and handsome brick architecture. Prestigious guests visited and spoke in the Walt Whitman auditorium. Eleanor Roosevelt received a standing ovation for her victory speech the day after John F. Kennedy was elected President. Allen Ginsburg came and read his poetry. It was well received. The Zen scholar and meditator Allen Watts came and spoke about the ease of meditation and liberation. From the audience I asked him if the same stage he was describing as liberation could be reached by drugs or alcohol. It was a silly question because I knew alcohol couldn’t produce any state of transcendental high. And he told me so. But he said psychedelic drugs could produce a state like satori, and I was surprised that he said it. It seemed too easy that something the monks could achieve only by years of austere practices could be achieved by taking a pill.

pp. 24-32

Sighting the fawn,

watching clouds pass overhead,

and you tromp and tromp

on the hardening ground.

Can’t pay attention to

the Lord in His names.

Outdoors is helpful,

but will I have to wait

many future births?

As the deer stands frozen, looks

at me but can’t see me, so I am

dumb to the sweetness of

hari-nama:

yet He’s with me as I walk.

Gunshots, loud and more of them.

So much trouble in each life,

and me with meager resources.

A disciple wrote me,

“You tell us to follow the rules

but we need to be hugged, your philosophy

doesn’t grow corn and run oxen.

People hurt us and play games,

so what are you going to do?

We don’t see you as the one who can heal.”

I go out the back door

into the woods,

come back healed but

not enough.

Who can help the deer?

On the hill the leafless trees

clacking in the soft wind.

A dry ache in spirit.

Spiritual words

can express everything

but I have no such words today.

The woods clack in the breeze

and I hope that my spirit can drink

and that Krsna will hear.

Those who showed up at mangala-arati:

me and Mathuresa,

a little kid in an orange dhoti,

Baladeva who cruised in overnight

in his Iveco truck;

Janaka returned from Atlanta, (the flower business

he was planning didn’t work out);

Strong Steve was there in his

long underwear shirt, and Acarya dasa, Bhubhrt,

Gudakesa

The main Persons are Radha and Damodara,

and Tulasi-devi who is growing to the left

searching after sunlight.

As we serve her, we gain love of Krsna,

and therefore we’ve come.

Walking on the road, I read His verse:

“When you have heard from the self-realized soul,

you will never again be in illusion because

you’ll know that everything is Krsna’s.”

I prayed that it would be true for me.

But when I tried another sloka—

how even the sinful can cross

in the boat of knowledge—

my mind went off to ten years ago—

Chris Murray said that Ted Kennedy

would like this verse

and a picture to go with it, by Chris’ wife, Kim.

They thought that Ted

would become U.S. President

but it never happened. I doubt Ted

would understand

the meaning of the Bhagavad-gita.

He’s a champion of the underdog,

but how will the sinners cross?

The answer is, by knowledge of Krsna.

But my attention span has snapped.

We talked in the meadow,

on the third day of the hunting season.

I said I don’t like to hear so many Krsna stories

when they’re without Prabhupada’s purports.

They make me unsure. He said he’s the opposite,

always after some new stuff.

But we both want the truth.

He read in Bhaktivinoda Thakura,

“No idea is false.”

But it’s all brought together in the Vedic literature

with its many centuries of faithful acaryas.

Jnana-sakti is a big man, affectionate,

a young devotee.

We’re both tied up to the Vedic truth.

And me his spiritual master?

I wanted to say,

don’t expect too much of me.

We talked about the deer.

I saw one limping.

He said he saw three does without their buck.

“Yes, they travel that way,” I said.

“I read it in Bambi,

their hatred and fear of man.”

Jnana-sakti winces: he’s vulnerable. He says

he didn’t read Bambi but recalls one scene

where the animals are fleeing from the hunters.

He mentioned the biography

of Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura.

“When I read that,” he said

“I felt I could confidently surrender

myself at his feet.”

We part, both in our orange hats.

I head into the woods, on warm wet ground.

If I see a hunter I’ll tell him.

Photos can’t catch Him,

you have to go and see Him.

Walk the road in moonlight

enter the building, hang up your coat.

Inside in the dark,

as the Deity doors open—

light pours from the altar,

flowery patterns of blue, red, yellow, white—

the gopis and Radha wear aprons—

I can’t describe it. Pujaris call it

“Their razzle-dazzle outfit.”

Damodara, beyond my words.

pp. 27-32

The moving hand sails on a Pandoro ferry on a smooth sea to France. When I go topside and look out at the expansive sea, I can’t help but recall a bit my life on the USS Saratoga. The sea is one thing and the Navy another. Bhakta Kevin, who was recently honorably discharged from the Navy, called it “prison life.”

Hand grip

nip

nipper. Land

mines wherever you

go those

unsavory memories and

images.

In Spain I could speak like this:

I know they like it when I speak of prayer, but my practice has shattered to pieces right now. Pray? I’d love to. Sometimes the prayer state is unattainable.

Right now I have to say, “What I do, that’s prayer”—and I mean reading, writing, chanting in an inward way. I could say my outer life has become inward. I’m establishing that I live mostly alone, and that that’s my life of prayer more than this technique or that method. If you’re always socializing, it’s very hard to be prayerful and inward.

Good

goops he

slipped again and tried to write

in a new language

(James Joycean?).

One of his devices is to join pictures to words—ideograms. Simply jump from one to another and tell the story in a poem.

Narada explains to Yudhisthira (and Sukadeva Gosvami to Maharaja Pariksit) that we should develop our relationship with Krsna whether it’s friendly, based on lust (such as the gopis’ which is brilliant and nonmaterial), or even based on enmity. Somehow or other, think of Krsna and we will be liberated. We will be qualified to perform eternal devotional service.

The world of Henry Adams

pipe-smoking, queer college student

1970s, the whirl of ISKCON’s

traveling men—radicals in

a spiritual movement

trying to pick up serious devotees wherever they go. We got a few good ones in the Midwest and California. Now I try to get those already caught involved in a loving relationship with Prabhupada. Bring them farther in. How serious they become is up to them. It doesn’t matter whether or not they live in a temple. That’s my preaching. I correspond with them.

I read in the intro to the Dover Thrift Edition of selections from Thoreau’s journal—the guy said that Thoreau used to gut his diary to form other books, such as A Week in Concord and Walden. Then he turned to leaving the diary intact and made that into a work of art. Thoreau had great trouble getting anything published, so how could he have expected his huge journal to be published intact? It wasn’t published during his lifetime, but almost immediately after his death that work was begun.

The editor goes on to say that Thoreau was convinced in his project. How wonderful that a person can retain conviction even without hope of reward. Emily Dickinson was the same. She sent a few poems to a prominent editor, but he wrote back with faint praise and said he couldn’t understand them. She wrote him a letter saying she would remain a “barefoot” poet.

I too should be convinced of what I am doing. A devotee writes to please guru and Krsna. He keeps their pleasure always in the forefront of his mind as the all-in-all. From that dedication he may see, even in his own lifetime, that some people appreciate what he is doing. Or he may meet only criticism. It doesn’t matter. He simple continues.

An author can’t pretend that he never thinks of what will happen to his writings after he dies. A devotee author hopes that others will continue to benefit from them, and that he will receive credit toward his own eternal devotional service. It would be folly to try to enjoy either present admiration or the admiration that might come after death, however. We are not meant to invest our emotions in material praise. My point right now is only to admire the selfless dedication of persons like Thoreau, Dickinson, and SK, and that their selflessness was not a shallow one but a determined individuality. It was not dependent on fame and glory.

Emily wrote:

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you Nobody—Too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell! they’d advertise—you know!

How dreary—to be—Somebody!

How public—like a Frog—

to tell one’s name—

the livelong June—

To an admiring Bog!

pp. 120-21

In this writing I am trying to be as honest as possible. Sometimes that includes admitting that even while on vraja-mandala parikrama, my mind goes elsewhere. Then why do I write about that?

My gut reaction to that question is that I have a strong desire to write about it. I see it as part of my all-around honesty. I can also justify it by taking on the instructor’s hat and saying that I am showing others how to jump off the different trains of thought to get back to Vraja. I have to admit further, however, that I am not only writing as an instructor but for my self-purification.

You know, we repeatedly hear the same lectures. Sometimes our lives are so formal, too formal, and filled with presentation and stiffness. I like to write freely to relieve myself of suffocation, just as I take off my hat, loosen my scarf, kick off my shoes, and speak with my friends. This all-too-human side of spiritual life is common to us, although we often maintain that our movement is meant to be more formal. Thus to speak openly can give relief. Acknowledging our own humanness can also make us more forgiving and accepting of it when we see it in others.

We can see this human side even when we remember Prabhupada, although for many devotees, it presents a dilemma. If someone asks me, for example, about Prabhupada’s 1974 European tour—I was Prabhupada’s secretary at the time—I have to admit I can’t remember much. What I remember most about that time is that I had jaundice and that I spent almost the entire time in my room. I remember worrying that I was inconveniencing Prabhupada. Once he even remarked to another devotee that if I was too ill, he would leave me behind when he went to Switzerland.

In other words, my memories of Prabhupada’s tour are more memories of myself. Yet if someone is willing to hear that without thinking I am trying to upstage Prabhupada, we can draw some interesting prabhupada-katha from it. In that way, whatever genuine emotions I had in relationship with Prabhupada will emerge. However, if we block out the reality because it doesn’t fit our stereotype of what reality should be, then such gems of real feeling will remain covered along with the unpleasant memories.

Nor do I think that the freedom to speak about what life is actually like in Krsna consciousness produces only unpleasant things. Much of it is pleasant, as we see the forgiving and lenient nature of the spiritual master who knows our hearts, who may or may not become angry with us, but who gradually leads us toward purity and krsna-bhakti.

So here’s some more honesty: I am actually sitting in a Crown Victoria LTD station wagon. The car heater is humming. I am thinking of my “policy” toward Radha-kunda—cautious love, inner awareness, intellectual acceptance that Radha-kunda is the most sacred place in the universe, respect for the unmanifest and the manifest. I keep a certain distance because familiarity breeds contempt, and I am not eligible.

pp. 97-101

The letter on your desk is to Locana dasa, 1971. It’s his first initiation letter. You advised him to attract the students at Berkeley. Give them prasadam and philosophy, you said. “We can challenge any nonsense philosophy. Socrates, Plato, Kant, Darwin—all of them . . . who have misled so many people.”

We laugh when we hear Srila Prabhupada smash them, but it’s not a joke. “Now it is your task to find them out and expose them so that the people may appreciate the real philosophy.” Be convinced. Sell books. “Kindly assist me in this great work and know for certain that by your sincerely working in this way, you shall very soon go back home, back to Godhead.”

Vrndavana is a wonderful place. I am your son and servant. My brain is half-blown out by misuse in my youth. The enemies of my mind—lust, anger, illusion, fear, envy—still attack me. I don’t know when I’ll be free.

Coming to sit with you

a few moments

before the door opens

and I admit that I am not

the only one.

Not the best or worst

but I make my claim.

Let me touch your feet

before someone else enters these rooms.

At least a few moments

each day

I want to be alone with you

Prabhupada, when I came into your room just now, several ISKCON matajis were talking animatedly in the center of your room. I think they were planning arrangements for your service here, but they kindly exited so that I could be alone. It’s a fact it would have been entirely distracting if I tried to sit in a corner while they talked in the middle of the room.

The letter on your desk is to Makhanlal, 1971. You wrote that you could not attend the San Francisco Ratha-yatra that year. You went there for three years in a row, but, “This time I have been very fervently requested to attend the London Ratha-yatra where they are expecting fifty-thousand … So it is not possible to attend both festivals.” You said you would visit San Francisco when you went to America. “So you should go on with the festival more enthusiastically, even in my absence.” You wrote this from Bombay, on your way to Moscow and then Paris.

Our spiritual master flying all over the world, writing us letters and giving us the hope of seeing him again. He also gave us encouragement and expected us to be answerable. There was no question of other gurus in those days. Our simple desire was to put on a festival or distribute his books or to preach somewhere, and to be accountable. He captured us, whether he was mellow and soft with us or acted like a military general.

You wear a garland of all roses and another of orange marigolds. Your desk lamp is on. Nothing is known to us of the future, and we know very little of the present. We are still stumbling out of the past. Impurities lurk in our hearts. I repeat this theme to remind myself of what I have to do to become more fit to serve you.

Srila Prabhupada, here comes one of your brahmacari followers. He is carrying a quilted saffron book bag. He prostrates himself fully before you, then leaves the room. Devotees notice me, an old-timer. Let me notice me like that way. Wake up, Satsvarupa, and live up to your heritage. Be humble, but exult in inner pride and satisfaction that Srila Prabhupada blessed you—not only you, but you too. Now do something with the blessing.

Readers will find, in the Appendix of this book, scans of a cover letter written by Satsvarūpa Mahārāja to the GN Press typist at the time, along with some of the original handwritten pages of June Bug. Together, these help to illustrate the process used by Mahārāja when writing his books during this period. These were timed books, in the sense that a distinct time period was allotted for the writing, during SDG’s travels as a visiting sannyāsī

Don’t take my pieces away from me. I need them dearly. My pieces are my prayers to Kṛṣṇa. He wants me to have them, this is my way to love Him. Never take my pieces away.

Many planks and sticks, unable to stay together, are carried away by the force of a river’s waves. Similarly, although we are intimately related with friends and family members, we are unable to stay together because of our varied past deeds and the waves of time.

To Śrīla Prabhupāda, who encouraged his devotees (including me) To write articles and books about Kṛṣṇa Consciousness.

I wrote him personally and asked if it was alright for his disciples to write books, Since he, our spiritual master, was already doing that. He wrote back and said that it was certainly alright For us to produce books.

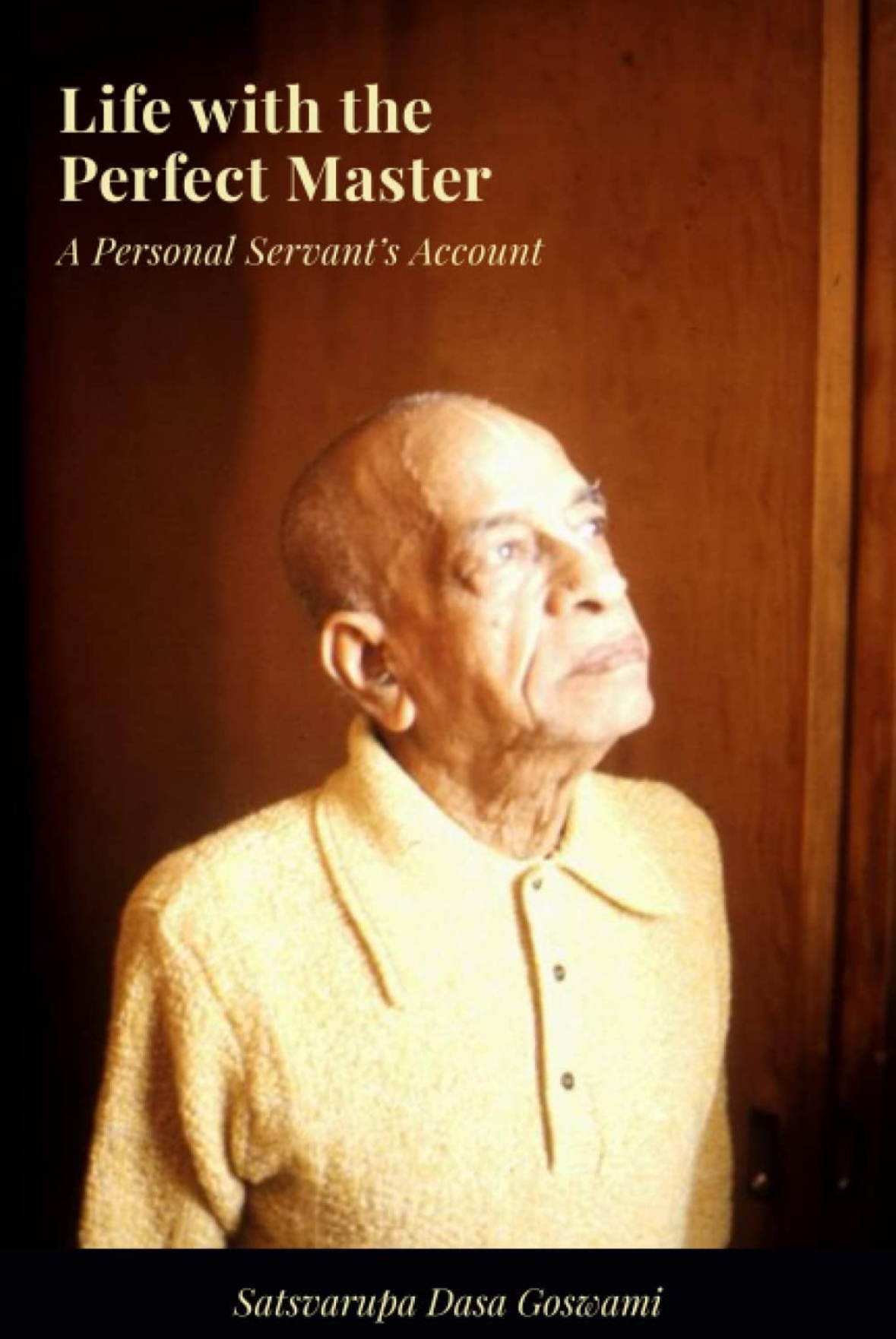

I have a personal story to tell. It is a about a time (January–July 1974) I spent as a personal servant and secretary of my spiritual master, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupäda, founder-äcärya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. Although I have written extensively about Çréla Prabhupäda, I’ve hesitated to give this account, for fear it would expose me as a poor disciple. But now I’m going ahead, confident that the truth will purify both my readers and myself.

First published by The Gītā-nāgarī Press/GN Press in serialized form in the magazine Among Friends between 1996 and 2001, Best Use of a Bad Bargain is collected here for the first time in this new edition. This volume also contains essays written by Satsvarūpa dāsa Goswami for the occasional periodical, Hope This Meets You in Good Health, between 1994 and 2002, published by the ISKCON Health and Welfare Ministry.

This book has two purposes: to arouse our transcendental feelings of separation from a great personality, Śrīla Prabhupāda, and to encourage all sincere seekers of the Absolute Truth to go forward like an army under the banner of His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda and the Kṛṣṇa consciousness movement.

A single volume collection of the Nimai novels.

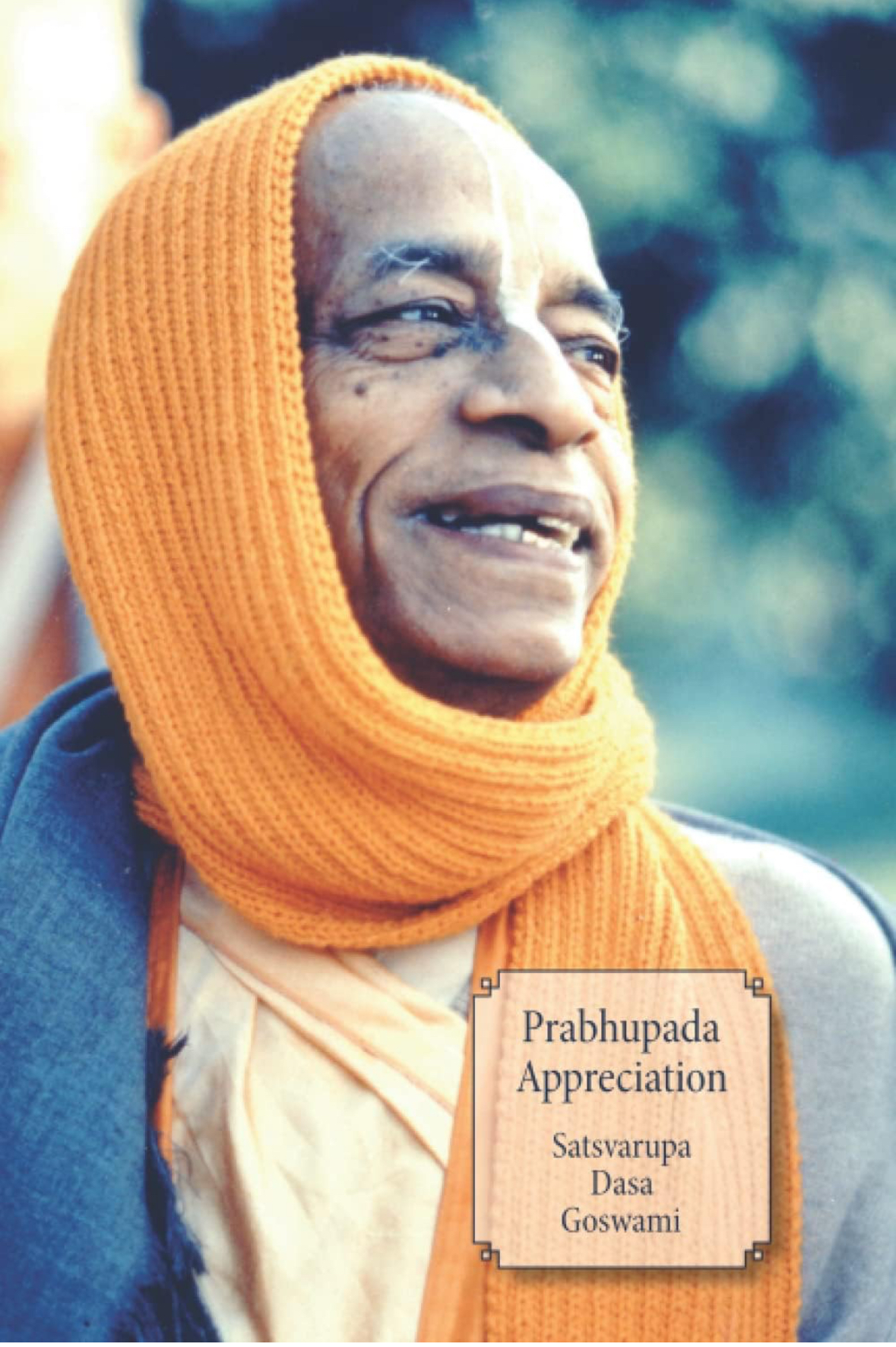

Śrīla Prabhupāda was in the disciplic succession from the Brahmā-Mādhva-Gauḍīya sampradāya, the Vaiṣṇavas who advocate pure devotion to God and who understand Kṛṣṇa as the Supreme Personality of Godhead. He always described himself as simply a messenger who carried the paramparā teachings of his spiritual master and Lord Kṛṣṇa.

Dear Srila Prabhupada,

Please accept this or it’s worse than useless.

You have given me spiritual life

and so my time is yours.

You want me to be happy in Krishna consciousness

You want me to spread Krishna consciousness,

This collection of Satsvarūpa dāsa Goswami’s writings is comprised of essays that were originally published in Back to Godhead magazine between 1966 and 1978, and compiled in 1979 by Gita Nagari Press as the volume A Handbook for Kṛṣṇa Consciousness.

This second volume of Satsvarūpa dāsa Goswami’s Back to Godhead essays encompasses the last 11 years of his 20-year tenure as Editor-in-Chief of Back to Godhead magazine. The essays in this book consist mostly of SDG’s ‘Notes from the Editor’ column, which was typically featured towards the end of each issue starting in 1978 and running until Mahārāja retired from his duties as editor in 1989.

This collection of Satsvarupa dasa Goswami’s writings is comprised of essays that were originally published in Back to Godhead magazine between 1991 and 2002, picking up where Volume 2 leaves off. The volume is supplemented by essays about devotional service from issues of Satsvarupa dasa Goswami’s magazine, Among Friends, published in the 1990s.

“This is a different kind of book, written in my old age, observing Kṛṣṇa consciousness and assessing myself. I believe it fits under the category of ‘Literature in pursuance of the Vedic version.’ It is autobiography, from a Western-raised man, who has been transformed into a devotee of Kṛṣṇa by Śrīla Prabhupāda.”

The Best I Could Do

The Best I Could DoI want to study this evolution of my art, my writing. I want to see what changed from the book In Search of the Grand Metaphor to the next book, The Last Days of the Year.

a Hare Krishna Man

a Hare Krishna ManIt’s world enlightenment day

And devotees are giving out books

By milk of kindness, read one page

And your life can become perfect.

Calling Out to Srila Prabhupada: Poems and Prayers

Calling Out to Srila Prabhupada: Poems and PrayersO Prabhupāda, whose purports are wonderfully clear, having been gathered from what was taught by the previous ācāryas and made all new; O Prabhupāda, who is always sober to expose the material illusion and blissful in knowledge of Kṛṣṇa, may we carefully read your Bhaktivedanta purports.

I use free-writing in my devotional service as part of my sādhana. It is a way for me to enter those realms of myself where only honesty matters; free-writing enables me to reach deeper levels of realization by my repeated attempt to “tell the truth quickly.” Free-writing takes me past polished prose. It takes me past literary effect. It takes me past the need to present something and allows me to just get down and say it. From the viewpoint of a writer, this dropping of all pretense is desirable.

Geaglum Free Write

Geaglum Free WriteThis edition of Satsvarūpa dāsa Goswami’s 1996 timed book, Geaglum Free Write Diary, is published as part of a legacy project to restore Satsvarūpa Mahārāja’s writings to ‘in print’ status and make them globally available for current and future readers.